"Astrotheology," it turns out, is an interpretation of astrobiology. It's theology about astrobiology. The term astrobiology was first proposed in 1953. In the 1990s, when microbial life was discovered in extreme environments on Earth, astrobiology got a boost from the idea that harsh conditions on other planets might not prevent life. We began to develop new methods to detect biosignatures.

The contemporary form of astrobiology emerged early this century -- and I first heard of it some 6 or 8 years ago. It struck me as funny -- both funny odd and funny ha-ha. How can there be a science of the life on other planets when we haven't yet found any life on other planets? But astrobiology is mostly a way of studying life on earth focusing on the conditions under which life emerged and under which it could have emerged and thus under which it might emerge somewhere else.

I want to start off, however, with some words about spirituality -- and go from there to what theology is -- and then we'll be ready to take a look at astrotheology, theology about astrobiology.

1. What Spirituality Is

Our sense of meaning and belonging: that’s what I’m talking about when I say spirituality. A healthy spirituality, a well-developed spirituality, is resilient: it provides one with an abiding sense of meaning and belonging in the face of life’s ups and downs. Spiritual development provides us with a measure of stability – perhaps even equanimity – when everything falls apart.

For most of the last 2,000 years of Western Civilization, it was understood that relationship to God was what provided such spiritual stability. Spirituality was assumed to be about a supernatural part of you resonating with a supernatural force of the universe. But if you take away the supernatural – if that drops away – there’s still the matter of what a person can do to cultivate the sense of life having meaning, the sense that we belong.

2. The Narrative and the Experiential

There’s a narrative component of spirituality – there’s a story that you have about who you are and what you’re doing here. That story might, for instance, start with the Bible. Some Christians say the Bible is the Greatest Story ever told. It feels to them like a great story because that story lays out the context within which life has meaning. It describes a world in which people can belong.

There’s also an experiential component of spirituality. There’s the words of the narrative we have about our lives, and then there’s the wordless awe and wonder.

It is in the interplay of story and experience – of words and the wordless – that our spirituality develops. That interplay is the source of whatever sense we have that life is meaningful, and that we belong.

In that interplay, at some points we find our narrative seeming to resolve some of the mystery. The story makes things feel less mysterious, more explained. (I say it feels more explained because nothing is ever really, objectively explained. We call something explained, or we tell ourselves that we understand it, whenever we’re simply tired of asking more questions about it, or we can’t see any further questions as likely to be fruitful.)

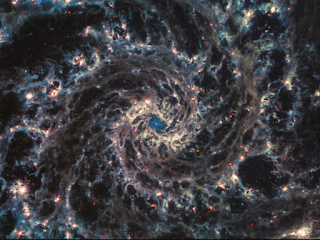

Narrative at some points eases the sense of mystery -- but at other points the narrative itself heightens our sense of mystery. When Carl Sagan’s 13-part PBS television series, "Cosmos" aired in 1980, he told a powerful story that heightened viewers sense of vast mystery.

Part of the Unitarian Universalist project is to attend to the findings of science as we put together our narrative about who we are – where we come from and what are we. It means our story is constantly changing as science changes.

3. How Old is Reality? How Big?

How long reality has existed is something religious narratives have generally offered some answer to. Our scientists understand the available evidence to pretty clearly establish that the universe is 13.8 billion years old.

This contrasts, on the one hand, with the Hindu Vedas, which put the current age of the universe at 155 trillion years. The Vedas depict history as a occurring in very large cycles, and enough of those cycles have happened to add up to 155 trillion years.

On the other hand, some forms of Christianity put the age of the universe at about 6,000 years. Our narrative from science puts the universe at 13.8 billion years old: a lot older than 6,000 years, and a lot younger than 155 trillion years.

In addition to the age of reality, religious narratives may also convey some sense of how big it is. For most of Western thought, there was the earth, and there were the heavens – up there, some leagues away. We now inhabit a universe we understand to be much, much bigger than that: about 90 billion light years across. How could it be 90 billion light years across when it’s only 13.8 billion years old? That’s because the universe is expanding faster than the speed of light (which, I didn’t know, but I learned that at our Science and Spirituality group). No object in the universe can move faster than light, but the space of space is getting larger at faster than light.

4. Stories, Like Space, Have Edges

And speaking of the edge of space, there’s an edge to our narrative, too. One of the fascinating features of this narrative – the story that imparts the sense that things make sense – most things, most of the time – and that we belong – is what we decide to leave unexplained. Our narrative universe of meaning and belonging has to have a boundary, just like our physical universe has an edge. The story has to have edges beyond which it doesn’t venture.

For traditional theism, we meet the edge of the story if we ask well, where did God come from? Traditional theism simply doesn't go there. The science narrative also has its edges.

Isaac Newton mathematically described the way gravity works. Attraction due to gravity is proportional to the mass of the objects, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. Boom. Drop the mic.

And people were like, but why? Why should mass be attracted to other mass – and if it is, why should that attraction be proportional to the amount of mass and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them? We’re just not going to go there, said Newton. He famously said, “hypothesis non fingo” – Latin for, “I feign no hypothesis.” I have nothing to say about that.

Centuries go by, and Einstein says that mass curves space, and gravity attraction is simply a matter of objects following that curve. OK, but why should mass do that? It just does. Why it does, we’re not going to go there.

Stories have to have a beginning, a middle, and an end – they have to have some stopping point. The science story, just as the traditional theist story, has its ending points.

5. What Theology Is

The large-scale narrative in terms of which we understand our life’s meaning, and our belonging, is theology. That’s what theology is: it’s the overall story from which we get a sense of meaning and belonging. Originally, theology was logos about theos – words about God. But that was when God was the central feature of everybody’s large-scale narrative. Theology today is any activity of constructing and revising our account – our story, our narrative – of meaning and belonging.

So Astrotheology, in particular, constructs an account placing contemporary space sciences within our story of meaning, purpose, and belonging. Astrotheology, as noted, piggy-backs on astrobiology – which examines life – bio – in the universe. Astrotheology is an interpretation of astrobiology.

6. Astobiology

Astrobiology’s first task is to define what life is, so we know what we’re looking for out there. But this turns out to be quite difficult. One of the key parts of our story about who we are, what it means to be us, is that we’re alive. What is that? What is life?

We don’t know. We can list some characteristics – we can say, well, life includes reproduction, growth, energy utilization through metabolism, response to the environment, evolutionary adaptation, and an ordered structure of anatomy. OK, that’s what life does. But what is it? Also, nonliving things do these things.

Life has structure and it grows. Crystals have structure, and they grow. Ah, but life reproduces. Does that mean if you’re not reproducing, you aren’t alive? Oh, but you COULD reproduce. Maybe not. Mules can’t reproduce, but they’re alive.

Life metabolizes – but so does your car – it breaks down fuel to release energy. Life reacts to its environment, but doesn’t everything? A mercury thermometer responds to its surrounding. A thermostat even responds to the temperature in the room by turning on the heat or the AC to CHANGE the temperature in the room.

Some have tried to define life using thermodynamics – for instance, Eric Schneider says life is a “far from equilibrium dissipative structure that maintains its local level of organization at the expense of producing environmental entropy.” OK -- but a fire also fits that description.

So: we don’t really know exactly what we’re looking for out there. We don’t know if we’ll know it when we see it. But we hope we will. And so we look. For the ancients as well as for us moderns, the stars light up the sky and the soul.

Is life a freak chemical event? Or is it a cosmic imperative – an “obligatory manifestation of matter, written into the fabric of the universe”? I don’t know.

7. Stephen Webb's Argument

Over a year ago, on Sun Mar 27, I preached a sermon called "Biology and Spirituality." I’ll review one of the points I made then, and then see if we can go the next step. I shared with you then the argument made by science writer Stephen Webb. Webb thinks that we’re alone in the universe – maybe not alone in terms of being alive, but alone in terms of having technological civilization. He says: There are 100 billion stars in our Milky Way galaxy. If we quite generously assume 10 planets per star, that would be 1 trillion planets.

Assume that 1 out of a thousand is habitable (has liquid water). Now we're down to 1 billion planets.

Assume that 1 out of a thousand of those has a stable climate over a long enough period for life to develop. Now we're down to 1 million planets.

Assume that on 1 out of a thousand of those microbial life gets started. Now we're down to a thousand planets.

And if 1 out of a thousand of those develops complex life? Now we're at just one planet in a galaxy the size of the Milky Way.

If 1 out of thousand of those develops sophisticated tool use, we're down to one planet for every thousand galaxies.

If 1 out of thousand of those develops science and mathematics, we're down to one planet for every million galaxies.

If complex societies and language develops that would be necessary to coordinate activities at the level of having a space program, we're down to one planet for every billion galaxies.

And if only one planet in a thousand manages to avoid disaster -- like a major solar flare, or a sizable asteroid, not to mention the inhabitants destroying themselves -- then we have only one out of a trillion galaxies. And since we estimate that there are only 200 billion galaxies in the observable universe, chances are, we're alone.

So goes the argument. Stephen Webb finds this a positive, even inspiring conclusion.

"For me, the silence of the universe is shouting, 'We're the creatures who got lucky. All barriers are behind us….’ And if we learn to appreciate how special our planet is, how important it is to look after our home, and to find others -- how incredibly fortune we all are simply to be aware of the universe, humanity might survive for a while. And all those amazing things we dreamed aliens might have done in the past, that could be our future."There's a certain awe and wonder to contemplating the vastness of space, the trillions of stars, and imagining ourselves the only ones able to be aware of the detail of this vastness. But there's also awe and wonder in contemplating that maybe we aren't alone after all.

8. Reconsidering Webb

Webb laid out his argument five years ago. I don’t know whether more recent discoveries would change his calculations. As of Wednesday, the count of confirmed exoplanets (planets around a star other than our sun) in the Milky Way was at 5,383. There are another 9,432 exoplanet candidates – that is, we have preliminary indication that there might be an exoplanet there, but we haven’t confirmed it yet.

Our Milky Way has about 200 billion stars, about one-tenth of them, 20 billion, are sun-like stars. NASA says about half of the sun-like stars have rocky planets in the habitable zone – that is, they could have liquid water. Some more optimistic NASA scientists estimate 75% of sun-like stars have habitable planets. So making it across the first barrier – habitability – we’ve got 10-15 billion exoplanets in the Milky Way. Stephen Webb thought we were already down to 1 billion at this stage.

The second barrier is stability – and it is remarkable that our Earth has the perfect sized moon at just the perfect distance for holding our axis stable. Planets such as Mars, for example, have an axis that wobbles all the way from horizontal to vertical, but Earth’s axial tilt varies only a little over 20,000 years, because of our moon. And this keeps our planet’s climate fairly stable – which is important for complex eco-systems to develop. But if we’re just talking about simple prokaryotic microbes, we don’t have to have stability. ere on earth, we’ve found microbes in extremes: from minus 35 degrees Celsius – way below the freezing point of water – all the way up to temperatures almost to the boiling point of water. So for life to just get started, a planet doesn’t need stability.

From what we’ve learned so far, there’s a good chance that there is microbial life on other planets. I’m not a biologist or an astronomer, but that’s what I piece together from reading people who are.

9. How Freakish Humans Had to Be to Develop Technological Civilization

But technological civilization seems, gosh, about infinitely less likely. Biologist Stephen J. Gould argues that humans are “a wildly improbable evolutionary event.” Earth has endured 5 mass extinctions that wiped out 70 to 95% of species then extant. The first mass extinction was 440 million years ago, and since then, there’s been one, on average, about every 100 million years. After each mass extinction, new and very different life forms emerged into the ecological space left behind. That recycle might have repeated a million or a billion times without ever producing the sort of species humans are.

We humans are pretty freakish. We are, basically, pretty intelligent on our own, but we make ourselves effectively many orders of magnitude smarter by our hypersociality. It's our ability to link our brains together in the fantastically complicated ways that we do that allows us to build civilizations.

Remarkably, crucial to this linkage is our agreement to share in certain fictions. Money is a fiction. It’s just pieces of paper – and not even that, these days – just electrons in your bank’s computer. But because we agree to treat it as real, it becomes real. Because we agree that such fictions as money, and corporations, and legal codes are real, we can coordinate our activities in ways we never otherwise could to build this civilization.

So we needed to have some individual intelligence, combined with a powerful social need to link brains together, combined with a willingness to just make stuff up and decide to collectively believe it. So maybe it's very unlikely that there is any other technological civilization, even in 200 billion galaxies averaging 200 billion stars each.

Or maybe there are other technological civilizations out there. We don’t know. We have a Search for ExtraTerrestrial Intelligence program – and when we say intelligence we don’t just mean intelligent like chimps or dolphins, or even like humans would be if we were just a little less hypersocial. They mean intelligence that can link up to greatly magnify itself – that can, through writings left behind, link even with brains that are dead – and that can agree to believe in fictions – and can thereby come at last to technological civilization.

If we discovered such Extra Terrestrial Intelligence, would it radically reshape what we think of ourselves? Would it undermine all our traditional religions? Some people think it would, but Ted Peters writes, “as soon as confirmation of ETI [Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence] is announced, we can forecast that church basements will be readied for a covered dish dinner to welcome aliens into our space neighborhood.”

10. The Theological Lessons

We don’t know what life there might be on other planets, and we probably won’t know within any of our lifetimes. But there is something we learn from this unfolding story -- some very important theological points from the current state of astronomy and biology.

One, it’s possible. Even if technological civilization on another planet is highly, highly unlikely, it is not impossible. Just that maybe is a decentering of human life. We decentered Earth: since Copernicus we've understood the Earth is not the center of the universe. Then we decentered our Sun: we learned that it's just one of billions of stars in our galaxy, and it's actually closer to the edge than to the center of the galaxy. Then we decentered our galaxy: we learned there were billions of other galaxies. We keep on decentering ourselves. This means that the meaning of our lives, our sense of belonging, cannot derive from being cosmically central. We've had to find other grounds of meaning and belonging.

Two, we don’t have to know. Or even believe. As our physics and astronomy advances, what gradually filters down into the understanding of us nonscientists is an increased capacity to be comfortable in this vast unknown, comfortable not having a belief either way. We are gradually training ourselves to appreciate our life in the mystery, not knowing what’s out there and not needing to know or claim to know.

Three, we’ve begun to learn from the story of species evolution that we have meaning and belonging just because -- somehow, and against the odds -- we are here. We are accidental products of a mindless, intentionless process. That theology inclines us toward an ethic: that all species that are here – or on some other planet -- just by virtue of being here, also have meaning, also belong. It all belongs. We don’t know what’s out there. But whatever it is, wherever it is, whenever it may become known to us – it belongs.

That willingness, that capacity, to apprehend the belongingness of beings even though we cannot imagine them, then reflects graciously back on ourselves. If they belong -- no matter what they are -- then so do we. No matter what.