George de Benneville, part 2

After his last-minute reprieve from execution, George de Benneville, still just 20 years old, moved to Germany for the next 18 years, studying medicine along with doing preaching tours through Germany and Holland. Toward the end of this period of German residence, when he had been treating patients as a doctor for about a year, he himself fell very ill. In a high fever, he felt himself die, and his spirit depart from his body. He was escorted through heaven, and then purgatory. As he later wrote: "I took it so to heart that I believed my happiness would be incomplete while one creature remained miserable." One of his escorts assured him that all creatures would be restored to happiness without exception.

When he awoke, he was in a coffin, having been declared dead 42 hours before. He sat up to speak and flabbergasted mourners helped him out of the coffin. He returned to life with a renewed mission to preach "the universal and everlasting gospel of boundless, universal love for the entire human race."

The next year, 1741, when de Benneville was 38, he sailed for America to bring the universalist gospel to this country. De Benneville settled in Oley, Pennsylvania where he worked as a physician and apothecary, while also continuing his Universalist preaching. Thus he lived and worked -- married and raised a family -- for 52 more years, until his death in 1793 at age almost 90.

“Honor the ocean of love” became his signature slogan. Though he was not a settled minister or the founder of churches, George de Benneville is often called the first preacher of Universalism in America, and he was an important early influence on its development.

NEXT: Universalism: James Relly to John Murray

Sermons, Prayers, and Reflections from First Unitarian Church, Des Moines, IA (2023-2025) and Community Unitarian Universalist Congregation, White Plains, NY (2013-2023)

2022-04-30

2022-04-25

Borders & Belonging, part 2

The book of Ruth is short -- just four chapters – a drama in four acts.

Act 1. It’s the time of the judges. A famine comes to Judah. Elimelech, his wife Naomi, and their sons Mahlon and Chilion cross borders and go to Moab. Elimelech dies. The two sons marry Moabite women, but then, after about 10 years, the sons also both die. Naomi packs up to return to Bethlehem. Her two daughters-in-law expect to go with her, but she tells them to return to their own mothers and remarry. One of them, Orpah, reluctantly does so. But the other, Ruth, pleads:

“Do not press me to leave you or turn back from following you. Where you go, I will go. Where you lodge, I will lodge. Your people shall be my people, and your God my God. Where you die, I will die – there will I be buried. May the Lord do thus and so to me, and more as well, if even death parts me from you.”So Naomi and Ruth cross the border and return to Bethlehem, and arrive at the beginning of the barley harvest.

Act 2. Word gets around Bethlehem of Ruth’s remarkable loyalty and devotion to Naomi. To support her mother-in-law and herself, Ruth goes to the fields to glean. As it happened, the field she goes to belongs to a man named Boaz, who, impressed by what he’s heard of the young woman’s devotion to her mother-in-law, is kind to Ruth. Ruth tells Naomi of Boaz's kindness, and Ruth continues to glean in his field through the remainder of barley and wheat harvest.

Act 3. Boaz, being a close relative of Naomi's husband's family, is therefore obliged by the levirate law (or may feel obligated by the spirit of that law) to marry Ruth to carry on his family's inheritance. Naomi sends Ruth to the threshing floor at night where Boaz slept, telling Ruth to "uncover his feet and lie down. He will tell you what you are to do." Ruth does so. Boaz awakes and asks her who she is.

She answers, “I am Ruth, your servant. Spread your cloak over your servant, for you are a redeeming kinsman.”

Boaz tells her there is a closer male relative. In the morning, Boaz sends Ruth home with six measures of barley, then he goes into the city.

Act 4. Boaz meets with the unnamed closer male relative whom he had mentioned. Boaz says, “Naomi is selling the parcel of land that belonged to our kinsman Elimilech. As the closest male relative, you have first shot at redeeming it if you want it.”

The relative says, “I will redeem it.”

Boaz says, “You will also be acquiring Ruth to maintain her dead husband’s name on his inheritance.”

Then the relative says, “I cannot redeem it for myself without damaging my own inheritance. Take my right of redemption yourself.”

So Boaz redeems the property, and Ruth. Ruth and Boaz marry. They have a son named Obed. We are told Obed will become the father of Jesse, and Jesse the father of David.

To understand what this story is doing in the Hebrew Bible, first we need to understand what Moab means to the Israelites. Moabites are despised. As Glenn Jordan explains:

“In Hebrew folklore Moab was stereotyped as a place lacking in hospitality, and with some justification. There is a memory preserved in the words ot the Torah from another time of hunger and distress. In Numbers 22, the Israelites, recently freed from Egypt, are travelling through the wilderness on the way to the land of promise and they camp in the land of Moab. There is a reference in Deuteronomy 23:4 to a request made by the people to the Moabites for bread and water. The king of the Moabites, Balak, terrified by the number of people he would be required to supply… refuses their request for aid and shelter. Balak even hires a man to pronounce curses on them as he expels them from his land.” (27)So, the Israelites do not like Moabites. They despise them with a special vigor beyond their general distrust of foreigners. The sentiment is codified in Deuteronomy 23:3:

“No Ammonite or Moabite shall be admitted to the assembly of the Lord. Even to the tenth generation, none of their descendants shall be admitted to the assembly of the Lord.”And Ruth is a Moabite, as the text continually emphasizes. Hardly does the text ever say “Ruth,” without saying “Ruth the Moabite.” At one point, Boaz's fieldhand even describes her as, “Ruth the Moabite,...from Moab” --just to emphasize that her country of origin is not to be overlooked.

Yet Ruth’s devotion, her lovingkindness to Naomi, is clear. She declares: "your people will be my people." When they get to Bethlehem, Ruth takes the initiative in providing for them, saying, “let me go to the field and glean among the ears of grain.” And, the story tells us, Ruth ends up the great-grandmother of King David, Israel’s greatest ruler. She makes a big contribution to Israelite history.

But does the Hebrew Bible really need this story illustrating that foreigners can be decent people who make a positive contribution so we shouldn’t be hostile toward them? The admonitions were already in Exodus:

“You shall not wrong or oppress a resident alien, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt.” (22:21)And in Leviticus:

“When an alien resides with you in your land, you shall not oppress the alien. The alien who resides with you shall be to you as the citizen among you; you shall love the alien as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt.” (19:33)Evidently that was not enough, and to see why, we need to look back to what was going on in Judah around the time when the Hebrew Bible was taking its form.

By about 601 BCE, the kingdom of Judah was a vassal state paying tribute to Babylonia. Judah made a series of attempts to escape Babylonian dominance. Nebuchadnezzar of Babylonia laid siege to Jerusalem in 597, and again, 10 years later, in 587. He razed the city, destroyed the walls, demolished Solomon’s temple, and exiled the Jews to Babylonia. About 50 years later, Persia conquered Babylon, and Cyrus, King of Persia, decreed that the Jewish people return to Jerusalem.

During the period of Babylonian captivity, the Hebrew Bible began to form as various oral and written traditions were brought together. Just after the exile, further writings were added – in particular the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. Ezra the priest and Nehemiah the governor were the two best-known leaders of the Jewish community in the years just after the return to Jerusalem. In the books for which they are named, we read that Ezra insists on obedience to the Mosaic law’s separation from non-Jews, and that Nehemiah encloses Jerusalem with a wall and purges the community from all things foreign in order to build a distinctive Jewish identity.

It's in that context that this little story of Ruth, which had probably been a part of the oral tradition for a couple of centuries, got written down and emphasized, so much so that it became scripture. I’m saying maybe the Book of Ruth is in the Hebrew Bible specifically to push back against the rather xenophobic outlook of Ezra and Nehemiah. As Glenn Jordan writes, there may be

“occasions in history when the proper response to the times is not another war or new legislation, not even an election, but a work of art. In this case, the process of gathering an oral account and committing it to writing stands in front of the juggernaut of history in an attempt to divert the hearts of people towards some lasting values, and to remind them of their better selves.” (47)So maybe that’s why this story is there: to address a felt need to counterbalance Ezra-Nehemiah. In the face of the insularity and division and the border-enforcing of Ezra and Nehemiah, we needed Ruth, the Moabite, the immigrant, the border-crosser, to call us back to our better selves.

There’s Nehemiah proclaiming, “We will not give our daughters to the peoples of the land or take their daughters for our sons” (10:30), but a few books away there’s Ruth the Moabite standing before us to say, “Excuse me?”

And while Deuteronomy had said, no Moabite shall be admitted to the assembly of the Lord even to the tenth generation, the Book of Ruth tells us that the great King David was just three generations down from a Moabite.

So if you're asking, "What can I do about divisions all around us, and the mistreatment of people on the the wrong sides of those divides?" and what you mean is, "What can I do to change those other people who are so foolish and pigheaded as to disagree with me?" then my answer is: I don't know if that can be done.

But if you're asking, "What can I do to commit myself to the open-hearted devotion and loving-kindness across borders that Ruth exemplified?" that is the much better question. And if that's your question, let me turn it back to you: What can you do? You yourself can best answer that -- if you set your mind to answering it. May that question, and not our fears, command our attention.

2022-04-24

Borders & Belonging, part 1

Everything needs a boundary to be a defined and definite thing. Dissolution of that boundary ends the thing, its contents spilling out and merging with the surroundings.

We need our skin to hold us together – but not to seal us off. We need to let in, and let out, air and nutrients – and the skin itself needs to be porous. The average human adult has 7 million pores on their skin: 5 million hair follicle pores that secrete oils, plus 2 million sweat gland pores. Your pores secrete and also take in – which is how, for example, nicotine patches work.

You have to have boundaries – definition. And there has to be a flow through those boundaries – just to be biologically alive. But we humans are also social – in fact, hypersocial – animals. We need communication, connection flowing in, out, and through. We need ideas and love to flow in, to flow out, and flow through us – or we perish.

Through our connections, we form ourselves into groups, and the group also needs a definition, a boundary – some way to identify itself and be identified as a group. We need to belong, and our belonging requires a sense of US. So borders, boundaries, and belonging are wrapped up in each other. You don’t know who you are if you don’t know whose you are.

But the group’s border also needs to be porous: to take in and to give out. Whether the group is a nation, or a congregation – a trade union, sports team, or a gender or ethnic identity -- its definition of itself cannot be rigid or static, but must be somewhat ambiguous, vague, and evolving -- without being too much so. How do we know the healthy balance?

For the last two months, Ukraine has been trying its darndest to defend its borders – to fight off and push out an incursion that threatens its existence. Ukraine right now needs to be focused on a certain excluding: namely, the excluding of Russian forces. But fending off a very real organized hostile takeover attempt is one thing. Delusions of takeover from imagined dangerous others are quite different.

Fear – for our individual person, or for the group which is our belonging – heightens focus on our border, on protecting ourselves by shoring up that border however we can. Fear grabs our attention, and when there’s a real danger, fear is functional. When the snarling grizzly bear is charging you, rational calculation and logical deduction are much too slow – not to mention, they won’t give you the shot of adrenaline you might need. We need fear. Natural selection wouldn’t have made us fearful if it weren’t useful. But fear, in order to be the rapid reaction stimulus that it is, can’t take the time to be very discerning. So we are prone to be fearful of imagined dangers.

Fear morphs from a useful tool, blaring a warning when needed, to a pervasive condition: consuming and debilitating. Here in the U.S., division and polarization tears us apart. There is fear of the other in anti-immigrant attitudes, and in the cruelty of our policies toward people who live in different, poorer neighborhoods. There’s fear of the other driving every form of white supremacy, misogyny, and colonialism.

Zach Norris’ book, Defund Fear – or, as it was originally titled, We Keep Us Safe – is our Unitarian Universalist Association’s Common Read this year: the one book selected for all Unitarian Universalists to read and talk about. Norris points out that what really keeps us safe is – or would be – good schools, good jobs, effective affordable health care, clean and safe drinking water and air, safe roads and bridges. Funding for what really keeps us safe has been eroding for decades.

Instead, we’ve been erecting a more and more pervasive framework of fear, the four key elements of which are deprivation, suspicion, punishment, and isolation. We’ve been erecting and fortifying borders to keep THEM away from US. This has only reduced our safety. Our fears grow and grow, fueling counterproductive reactions that further reduce our safety in a vicious cycle.

Instead we need to cross borders, reach out to whoever is, or has been perceived as, OTHER. WE keep us safe – as the book’s original title says – and we can do so only if we embrace a larger WE instead of fearfully shrinking our WE. As you read the book, you might think to yourself: OK, I get the problem. But what do we do about it?

Norris has a number of recommendations, which he summarizes at the ends of chapters 5, 6, and 7, and those are indeed all worth our support. But sometimes when we ask “what do I do about it?” – or “what does our congregation do about it?” – the question behind the question is: "How do I make other people agree with me? How do I change THEM?" We think: “I see the problem; I am not the problem. It’s those other people, people who watch the TV news of that reprehensible network, and who vote for the candidates of that reprehensible political party." Thus the war between relatively privileged red America and relatively privileged blue America upstages the needs of the more-often-politically-disengaged poorer communities most at risk.

The challenge for us is to find ways to cross two different borders – to open our hearts across the red/blue divide and across the class divide. “How do we change the system?” is a good and important question, but today I want to talk about changing ourselves. I’m not going to go into detail – we will each have different details. I’m just going to call to mind an old, old story – possibly familiar to you – about a woman who did cross a border, and the difference it made. Perhaps it will inspire you to creatively imagine a way that you might reach, and step, across a border that you have for too long treated as impermeable.

The story is that of Ruth, the Moabite, who crossed borders to stay with her mother-in-law Naomi as she returned to Bethlehem in Judah. I’m inspired to bring that story to our attention this morning because of the work of Padraig O Tuama and Glenn Jordan, two Irishmen who led workshops bringing together people across the divisions of the Brexit issue. In the face of the deep and wide social and political divisions, O Tuama and Jordan led people through an exploration of the Book of Ruth. The story of her border crossing helped participants cross the borders that separated them from others.

O Tuama and Jordan were looking for

“a story that might lead us to say things other than the things we are shouting at each other in the letters section of newspapers, comments sections of websites and social media, shouty parts of shout programs on radio and television” (Borders & Belonging: The Book of Ruth: A Story for Our Times xii).In these polarized times, O Tuama and Jordan asked: “Can we be held in some kind of narrative creativity by a story whose origins we do not know?” The Book of Ruth, they found, offered just such a container of narrative creativity.

2022-04-23

UU Minute #84

George de Benneville, part 1

The first Universalist of note in America was George de Benneville, born in London to parents of French Huguenot nobility who had fled religious persecution in France. At age 12, George went to sea briefly as a midshipman in the Royal Navy. While docked in Algiers, George witnessed natives tending to an injured comrade, cleansing his wound and making supplications to the sun. Tears in his eyes, young George thought, “Are these Heathens? No, I confess before God they are Christians, and I myself am a Heathen!”

He later wrote:

At age 17, he went to France to preach this Universalist gospel. The Catholic religious authorities of France were not receptive. Landing in Calais, de Benneville was soon arrested, briefly imprisoned, then banished from the city.

In Normandy he preached to an underground group of Protestants, the Camisards, for two years, was arrested again and condemned to death. As he knelt on the scaffold awaiting the stroke of the executioner's axe, a reprieve came through from King Louis XV, based on de Benneville’s French noble heritage.

For the further adventures of George de Benneville, be sure to catch our next thrilling episode.

NEXT: George de Benneville, part 2

The first Universalist of note in America was George de Benneville, born in London to parents of French Huguenot nobility who had fled religious persecution in France. At age 12, George went to sea briefly as a midshipman in the Royal Navy. While docked in Algiers, George witnessed natives tending to an injured comrade, cleansing his wound and making supplications to the sun. Tears in his eyes, young George thought, “Are these Heathens? No, I confess before God they are Christians, and I myself am a Heathen!”

He later wrote:

“It had been my first lesson in understanding that the heart of religion is how people treat one another, not always what they say they believe.”Back home, he had a vision of himself “burning as a firebrand in hell.” For more than a year he felt oppressed by unforgiveable sins. Then, a second vision: Jesus telling him he had been redeemed and was forgiven. If even he could be saved, he felt convinced, “I could not have a doubt but the whole world would be saved by the same power.”

At age 17, he went to France to preach this Universalist gospel. The Catholic religious authorities of France were not receptive. Landing in Calais, de Benneville was soon arrested, briefly imprisoned, then banished from the city.

In Normandy he preached to an underground group of Protestants, the Camisards, for two years, was arrested again and condemned to death. As he knelt on the scaffold awaiting the stroke of the executioner's axe, a reprieve came through from King Louis XV, based on de Benneville’s French noble heritage.

For the further adventures of George de Benneville, be sure to catch our next thrilling episode.

NEXT: George de Benneville, part 2

2022-04-22

Easter! Passover! Ramadan! Liberation! part 2

Two ideas in the Passover festival are central:

- It is a celebration of freedom. Passover is known as “The Season of our Liberation.” It commemorates the escape from enslavement in Egypt.

- It is a call to hospitality.

These are interrelated and intertwined. The human psyche has three basic categories: ME, US, and THEM. Exodus tells about the liberation of an US. As a story initially and primarily told by Jewish people to Jewish people, it’s the story of how WE were enslaved. Physical needs for food, clothing, shelter, or sleep were often inadequately met. Worse, human needs for respect, autonomy, trust, dignity, worth, and self-expression were systematically and extremely denied – through regular use and constant threat of inflicting great pain and humiliation, typically the lash, applied in a way sometimes punitive and sometimes simply random, though always ostensibly punitive. It was an utterly miserable existence.

That’s the miserable existence WE were stuck in. But WE got out of it. WE, as a people, as an US, achieved political liberation – a system of some modicum, at least, of rights and liberties. It was not at all a democracy, and a read through the books of the prophets illustrates how the Israelites struggled constantly for centuries with issues of oppressing each other. But the oppressors were US now – we shared a bond of culture and of worship -- and their cruelties were less systematic, less extensive, and usually less extreme. So we were free. Or at least, "free."

When political liberation happens – when a people enjoy some rights and liberties, when physical needs can be met and those human needs -- respect, autonomy, trust, dignity, worth, and self-expression – are not systematically denied, people become susceptible to different kind of bondage. We are likely to want to guard what we have. We can become, essentially, enslaved to self-protective habits and desires of the moment. Life can come to feel bereft of meaning, even though we have autonomy.

The tradition of liberation that begins with political liberation from external oppressors must then turn to personal liberation from our own internal oppressors. When US is no longer oppressed by THEM, ME may still be oppressed by ME-self. The internal voices of self-protection and of satisfying desires of the moment drown out the voices that want our life to mean something more than its own security and gratification.

Thus the Passover Seder tradition, the Haggadah text, addresses this liberation, too. “Let any who are hungry come and eat” is as central a message as “we escaped our enslavement in Egypt.” To liberate US, we get away from the THEM that oppresses. But then, to liberate ME – that is, liberation from internal voices of self-protection and desire – we must turn toward THEM, turn toward those who are other, turn with an open heart toward those, whatever their culture, who we can help. We make our lives meaningful – liberated from the abyss of meaninglessness – by reaching out to help, to share with, any THEM that is need.

Rabbi Hillel said it succinctly: “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? If I am not for others, what am I? And if not now, when?” Yet another way to say it is that gratitude and generosity are intrinsically linked. The Seder exercise of imagining yourself as personally coming forth out of Egypt is an exercise in gratitude. It fills us with thanksgiving for the freedoms we enjoy. And the concomitant of gratitude – the action that confirms and solidifies and sustains gratitude – is generosity. So the gratitude of escaping slavery very naturally segues into the generosity of “let any who are hungry come and eat.”

Inspect your own experience. What does being ungenerous – being stingy – feel like? Does it not feel like a kind of ungratefulness Isn’t the miser necessarily also an ingrate (whether in the form of your own inner miser, or someone else)? To turn toward generosity, toward radical hospitality, toward open-heartedness toward THEM who are not US – this gives our lives richness and meaning. It is liberating.

Political liberation without radical hospitality becomes personal bondage. Hospitality to the other is what you can do right now for collective liberation. And the Passover message is that what you do for collective liberation serves also your personal liberation.

It’s a message also found in Ramadan, to which we now turn. For Muslims, all scripture was revealed during Ramadan, and it is to the celebration of scripture, or Mohammed’s revelation of that scripture, that this holy month is dedicated. It’s a time of fasting and prayers – which highlights the personal liberation of connecting to the ultimate. It’s also a time of community and heightened charity – which highlights the linkage of individual liberation to engagement with the welfare of others.

During the 30 days of Ramadan, Muslims are enjoined to read the entire Quran, which is divided into 30 parts – so, one part per day. Believers are called to stand up for justice and bear witness to the truth, as the Quran says, “even if it is against yourselves, your parents, or your close relatives.” The Quran says to never allow “hatred of others to lead you away from justice.” It tell us to “be a community that calls for what is good, urges what is right, and forbids what is wrong.” It tells us “to free the slave, to feed at a time of hunger an orphaned relative or a poor person in distress, and to be one of those believe and urge one another to steadfastness [in doing good] and compassion.” It prescribes almsgiving for the poor and needy (9:60) and an ethic of charity that affirms and restores the dignity of socially neglected people (2:261—274). It tells us to defend the oppressed even if it means putting our own lives at risk.

This is the social justice message of the Qur’an. The Quran also includes prohibition of usurious loans, giving short measure in one’s business dealings, exploiting orphans, acting like tyrants, or spreading corruption. There’s a recognition here, as in Judaism and Christianity, that our own liberation is tied up with the liberation of others.

Emma Lazarus, writing in 1883, said: “Until we are all free, we are none of us free.” Fannie Lou Hamer put the point a tad more pithily: “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.” Our own personal liberation is bound up with ending all systems of domination.

We come again to what would appear to be the Catch-22 alluded to earlier: You can’t be free unless you free others. Yet you can’t free others unless you yourself are free. But this conundrum dissolves when we simply observe that liberation is not all or nothing. We are part-way liberated.

We are part-way liberated as individuals – though still held in some thrall to our addictions, attachments, habits, fears. We are part-way liberated as a society – we have come a long way from the absolute monarchies in which no one had rights or a vote but the king – though still held in some thrall to white supremacy, patriarchy, homophobia, generational wealth, meritocracy.

Such personal liberation as we have can be used to advance collective liberation. Such collective liberation as our society has lays the groundwork for us to take the next steps on our personal liberation journey. So bring out that festal bread and sing songs of freedom. And may we, along with the Earth in springtime, awake again.

2022-04-17

Easter! Passover! Ramadan! Liberation! part 1

Today is a holy day in the Christian tradition. It’s Easter.

This week is a holy week in the Jewish tradition. Passover began last Friday evening and lasts until next Saturday evening.

And this month is a holy month in the Islamic tradition. It’s the month of Ramadan.

We have three great traditions overlapping, and each tradition offers us a story, redolent with meaning and possibility whether we are adherents of the faith tradition from which it comes or not.

At Community UU, our theme of the month for April is liberation, and our journey groups are exploring this issue, and looking at what sorts of things from which a person might need to be liberated.

- There have been and are groups that are oppressed, beaten down. Liberation is about ending forms of enslavement, oppression and injustice. Liberation calls for dismantling the systems of colonialism, patriarchy, and white supremacy.

- There’s also the issue of personal liberation – liberation from our own irrationalities, fears, bad habits, preoccupations, cravings, and ego defenses. These constraints may constitute a kind of prison -- though sometimes quite a comfortable prison -- even when there are no iron bars.

The Easter story has often been presented as a story of personal liberation – liberation from, in the Christian argot, the bondage of sin. In other words: we aren’t always our best selves. Heedless pursuit of passing desires can feel like a kind of bondage. Or our habits of self-protection constrain us from a more fulfilling joy -- and may lead us make moral mistakes. According to the doctrine of substitutionary atonement, Jesus' suffering on the cross redeems us from all of that. Jesus suffered and died that we might have life (i.e., he substituted for us in order to atone for us).

Unitarians have been rejecting substitutionary atonement for centuries. As our UU Minute segments have noted, Fausto Sozzini in the 16th-century, Joseph Priestley in the 18th-century, and William Ellery Channing in the 19th-century were among prominent Unitarian thinkers to critically examine the doctrine of substitutionary atonement and find it unsupported by either the Bible or reason. The implication of substitutionary atonement is that real love manifests as complete submission and self-sacrifice. God required of Jesus -- and may sometimes require of us -- passive acceptance of violence. If that sounds to you like a dangerous and harmful theology, I agree.

The message of Jesus’ ministry was not an exclusive attention to individual bondage to sin. He speaks often of something generally translated as “Kingdom of heaven” or “Kingdom of God.” In Matthew, the phrase is usually "kingdom of heaven," while in Mark and Luke it's usually "Kingdom of God." (Neither phrase appears in John.) Jesus spoke Aramaic, and we have no records of his actual Aramaic words. What we have is the Greek in which the Gospels were written. The Greek word typically translated as “kingdom” is basileia. The basileia Jesus is talking about – the kingdom of God, or, better, the kin-dom of God -- is a siblinghood of radical acceptance, a social arrangement based on our universal kinship and oriented toward justice. Theologian Robert Goss writes of:

"the basileia, the reign of God which signified the political transformation of his society into a radically egalitarian, new age, where sexual, religious, and political distinctions would be irrelevant. Jesus acted out his basileia message by standing with the oppressed and outcasts of society and by forming a society of equals."For Goss, the resurrection represents God’s endorsement and confirmation of Jesus’ basileia message. The resurrection reveals God’s orientation toward the excluded.

In Luke 17, verses 20-21, we read:

“Once Jesus was asked by the Pharisees when the kingdom of God was coming, and he answered, “The kingdom of God is not coming with things that can be observed; nor will they say, ‘Look, here it is!’ or ‘There it is!’ For, in fact, the kingdom of God is among you.” (NRSV)Other translations give, “the kingdom of God is within you,” and in this translational difference we have the two sides of liberation. If liberation is within you, the emphasis is on personal liberation from the psychological constraints of our irrationality, anxiety, ego defensive habits – bondage to sin; Jesus is saying you have it within you to break free from patterns that disconnect you from joy. If liberation is among you, the emphasis is on social liberation from forms of inequality; Jesus is saying that the liberation we seek is to be found in our togetherness, in the relationships of beloved community.

In fact, the original Greek preposition here is entos (“in the midst of”), which might suggest either within or among. A translator might reasonably go either way. In truth, it is both at once. The basileia is both within you and among you: within us each, individually, and among us, collectively. It must be both at once – neither the personal nor the social by itself will suffice. It’s our psychological bondage to counterproductive strategies of self-protection that creates and sustains structures of inequality. At the same time, it’s the sociopolitical structures of domination that create and sustain the bondage of irrational self-protection strategies. Reversing that feedback loop will require working on both sides at once. It will require doing what we can to liberate ourselves from clinging fears and attachments. At the same time, it will require doing what we can to dismantle the structures of social domination that engender individual self-constraining thinking.

A picture of the two sides of liberation at work is presented in the Passover story. We'll look at that in part 2.

2022-04-16

UU Minute #83

Universalism: Beginnings

We move now from our Unitarian story to the Universalist side of our heritage. Universalism gets its name from Universal salvation – that everyone goes to heaven and there is no hell. The early Universalists did, however, believe in purgatory – a temporary period of purging, purifying and cleansing before ultimate union with God.

Through Christian history, the concept of hell has been a mixture of attempting to discourage sin and a perverse schadenfreude enjoyment for the elect. 2nd-century Christian theologian Tertullian (155-220) wrote that the joy of heaven consisted in being able to look down into hell and watch the torments of the damned. In the 13th-century, Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) also argued that the saints in heaven would be able to view the sufferings of the damned – “in order that the happiness of the saints may be more delightful to them.”

Yet there have also been Christian thinkers from early on who found incongruous the notion that a loving God would condemn to eternal torment creatures of God’s own making.

In the 18th century, London-born preacher and medical student George de Benneville had a near death mystical experience that convinced him of Universal salvation. For more on de Benneville sure to catch our next thrilling episode.

NEXT: George de Benneville, part 1

We move now from our Unitarian story to the Universalist side of our heritage. Universalism gets its name from Universal salvation – that everyone goes to heaven and there is no hell. The early Universalists did, however, believe in purgatory – a temporary period of purging, purifying and cleansing before ultimate union with God.

Through Christian history, the concept of hell has been a mixture of attempting to discourage sin and a perverse schadenfreude enjoyment for the elect. 2nd-century Christian theologian Tertullian (155-220) wrote that the joy of heaven consisted in being able to look down into hell and watch the torments of the damned. In the 13th-century, Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) also argued that the saints in heaven would be able to view the sufferings of the damned – “in order that the happiness of the saints may be more delightful to them.”

Yet there have also been Christian thinkers from early on who found incongruous the notion that a loving God would condemn to eternal torment creatures of God’s own making.

- Origen (185-253) is most often named as the first Christian universalist. He was firmly convinced that “all human souls will ultimately be saved” and “united to God forever in loving contemplation.”

- Clement of Alexandria (150-215) seems to have viewed punishment after death as medicinal and therefore temporary before eventual elevation to heaven.

- Gregory of Nyssa (335-395) is interpreted by many as a Universalist.

- Isaac of Nineveh (613-700) in the 7th century was an advocate of Universalism.

In the 18th century, London-born preacher and medical student George de Benneville had a near death mystical experience that convinced him of Universal salvation. For more on de Benneville sure to catch our next thrilling episode.

NEXT: George de Benneville, part 1

2022-04-11

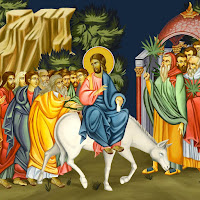

Palm to Palm, part 2

In this part, we'll look at two further matters in the Palm Sunday story: the acquisition of the colt, or donkey, and the bit about the stones shouting out.

So, what about that stolen colt (donkey)? Jesus sends his disciples off to fetch him a ride, telling them “If anyone asks you, ‘Why are you untying it?’ just say this, ‘The Lord needs it.’” It’s possible Jesus has made the consensual arrangements in advance to borrow the animal, though none of the Gospels suggests any such thing. To all appearances, they steal the colt.

We know this Jesus is not above crime. He acts illegally when he overturns the tables outside the temple. The Jewish and Christian scriptures include many examples of law-breaking for the sake of a higher justice.

“Moses also begins his leadership with crime, dispatching the Egyptian overseer to protect an enslaved person. Rahab begins her leadership with the crime of harboring fugitives. Daniel begins his leadership with the crime of refusing to eat the king’s diet. Esther commits the exact opposite of the king’s decree by appearing before him. Mary begins her leadership with the crime of getting pregnant by someone other than her betrothed.” (Casey Overton)Property laws primarily protect the interests of the propertied. In many cases the wealth was acquired through injustice, and property law enshrines and preserves that injustice.

Jesus throws his lot in with the vulnerable, and declines to be constrained by laws that serve only the interests of the rich. Remember Anatole France’s ironic line. Writing in the 19th century, he said:

“The law, in its majestic equality, forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal loaves of bread.” (The Red Lily, 1894)Yes, the law is framed to be irrespective of class, but it’s written to forbid only what the downtrodden need to do. Casey Overton’s Palm Sunday reflection asks us:

“What would it mean if, instead of chastising rule-breakers among us, we press charges against the rules themselves which have made liberation untenable? What would it mean if we began to hallow not just the political prisoner but the disenfranchised dealer benefiting from an alternative economy and heterodox heretics and other revolutionaries who dare to hold the law in the lowest regard? So here’s to the misfits and miscreants. Here’s to all the people who break the rules because they know those rules break the people. May we reject the colonial category of the 'criminal' in governments as well as our interpersonal dealings with the 'outlaws' in our communities. May we begin to honor you misunderstood messengers for the wells of wisdom that you are. May our houses of worship be a refuge for you when the empire retaliates.”I am not calling for lawlessness. I am calling for critical examiniation of how many of our laws really have anything to do with public safety. How much of our legal system is devoted to incarcerating the poor and people of color, while the wealthy whites who commit crimes that really do endanger public safety consistently do so with impunity?

Finally, in our exploration of the Palm Sunday story, let us consider those stones mentioned at the end of the passage. Jesus’ procession is evidently noisy. The disciples are being loud. Then, as Luke reports:

“Some of the Pharisees in the crowd said to him, ‘Teacher, order your disciples to stop.’ He answered, ‘I tell you, if these were silent, the stones would shout out.’”At one level, he’s saying this is a party that cannot be stopped. It’s also a reminder to us that the Earth bears witness. A story from another tradition tells of Siddhartha Gotama, known as the Buddha, being challenged: on what authority do you teach as you do? Gotama – the Buddha – simply reaches out and touches the ground. The Earth is his authority. The Earth bears witness. The stones shout out the story.

What story do the stones tell? The Hebrew Bible, too, includes references to the Earth itself, the stones, speaking for Justice. In the book of Habakkuk, one of the twelve minor prophets in the Hebrew Bible, the prophet cries:

“Alas for you who get evil gain for your house, setting your nest on high to be safe from the reach of harm! You have devised shame for your house by cutting off many peoples. You have forfeited your life. The very stones will cry out from the wall, and the plaster will respond from the woodwork.” (Habakkuk 2: 9-11)Today the Earth cries out the story of our desecration. Casey Overton says:

“In response to the colonizers’ disregard for consent, Earth has been in escalating protest against her ongoing enslavement and alienation from her indigenous caregivers. We can gratefully receive this passage as a reminder that the prophetic tradition includes conversation with the earth and concern for her perspective.”And at yet another level, Jesus is telling us what we can hear if we get quiet. After the noisy party-revolution of which I spoke in part 1, the Palm Sunday story now invites us into a quiet time – a time of listening, of attending. "I tell you, if these were silent, the stones would shout out," says Jesus. That is, in the silence, the shouting of stones may be heard. We often do not hear them over the noise of our chatter – the chatter of our tongues or the chatter that goes on in our minds when our tongues are still.

If we quiet our minds from the preoccupations of ego, we can hear the stones speak. They are shouting their existence. They are shouting continuously the glory of creation of which they partake. We have to be silent to hear it. In the silence we hear the Earth and all her creatures – the abundance and profligacy of life, yet also the groaning of pain from the damage being done to the climate, the destruction of habitat, the loss of species diversity.

We are called to a revolution of liberation from all that oppresses and discriminates. It is not a revolution of soldiers in military hierarchy inflicting violence and death. What does this revolution look like? There is no single look.

It looks like hands reaching out to help, to provide for – hands connecting, palm to palm, in compassion. It looks like a party, a raucous celebration. And it looks like being very quiet and listening, listening.

This is the message of Palm Sunday. Amen.

2022-04-10

Palm to Palm, part 1

Reflections Upon Palm Sunday

The Palm Sunday story of entrance into Jerusalem is mentioned in all four gospels. Here's the version from Luke 19: 28-40

After he had said this, he went on ahead, going up to Jerusalem. When he had come near Bethphage and Bethany, at the place called the Mount of Olives, he sent two of the disciples, saying, “Go into the village ahead of you, and as you enter it you will find tied there a colt that has never been ridden. Untie it and bring it here. If anyone asks you, ‘Why are you untying it?’ just say this, ‘The Lord needs it.’” So those who were sent departed and found it as he had told them. As they were untying the colt, its owners asked them, “Why are you untying the colt?” They said, “The Lord needs it.” Then they brought it to Jesus; and after throwing their cloaks on the colt, they set Jesus on it. As he rode along, people kept spreading their cloaks on the road. As he was now approaching the path down from the Mount of Olives, the whole multitude of the disciples began to praise God joyfully with a loud voice for all the deeds of power that they had seen, saying, “Blessed is the king who comes in the name of the Lord! Peace in heaven, and glory in the highest heaven!” Some of the Pharisees in the crowd said to him, “Teacher, order your disciples to stop.” He answered, “I tell you, if these were silent, the stones would shout out.” (NRSV)Today is Palm Sunday. What is that to us? What are we – we 21st century Unitarian Universalists who may or may not identify as Christian – to make of Palm Sunday?

Not a lot, usually. In past years, we have merely acknowledged that it was Palm Sunday, but said nothing more about it. We have not looked into what significance the story of which today is, by convention, the anniversary, might have for our own spiritual lives.

Scholars are divided on whether Jesus of Nazareth died in the year 30 or the year 33. We know essentially nothing of what he taught or did other than what was recorded in Gospel accounts the earliest of which were written over a generation after he died, and the Gospel of John not until 80 or 90 years after he died. In those gospels there’s a story about a prophet, on the Sunday before spring’s first full moon, entering a capital city in apparent triumph.

Maybe Jesus knew the danger. We know that after this entrance, as the story unfolds, things will quickly go badly for him. He’ll be arrested on Thursday, and by Friday evening he will be dead, killed in a gruesome and agonizing execution designed not merely to kill a person but to humiliate anyone associated with that person.

But at the time of his entrance, he seemed to be well received. The people welcome him enthusiastically. Jerusalem was swelled with pilgrims, in town for the Passover festival. The gospel of John reports,

“the great crowd that had come to the festival heard that Jesus was coming to Jerusalem. So they took branches of palm trees and went out to meet him, shouting, 'Hosanna! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord — the King of Israel!'” (John 12:12-13, NRSV)Only John, of the four gospels, actually mentions Palm trees in this connection. In many Christian churches today, palm fronds, or other leafy branches will be passed out to worshipers. There may be a procession in which palm fronds are carried. The palm fronds, or other tree branches, are blessed and then taken home and kept in the icon corner or next to a a cross or crucifix until the following Mardi Gras – Shrove Tuesday – when the branches are brought back to church where they are ritually burned for ashes used in Ash Wednesday rituals.

But what of the story at the base of all this? For one thing, what do we make of the monarchical references – the proclamation of being a king, the language of superiority, and ruling over -- the apparent privilege of being able to take some one else’s colt (or a donkey, depending on the gospel), without payment or compensation, but simply because “the Lord needs it.”

In the New Testament, Jesus is called, by gentiles, King of the Jews. He’s called that by the Magi who visit the nativity scene, and called that again at the end of his life – by Roman soldiers and Pontius Pilate. By his Jewish followers, he’s called Christ, which means messiah, which means anointed one, where anointing with oil is the ritual of coronating: a king. For us WEIRD folk – meaning those of us in Western Educated Industrialized Rich Democracies -- the idea of a King hardly seems progressive.

But there’s a different way to see this entrance. Some commentators see Jesus’ mode of entry as a subversion – not an appropriation or imitation of a royal procession, but a parody of royalty. Robert Brawley, for instance, writes that:

“Riding a donkey over his disciples clothes, Jesus parodies royal parades. . . . [He] caricatures military acclamations.” (Fortress Commentary on the Bible: The New Testament)After all, consider what else the Gospel writers tell us about this prophet, Jesus. Jesus’ ministry has emphasized good news for the poor and oppressed.

This is the prophet who preached:

“Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God....But woe to you who are rich, for you have received your consolation.” (Luke 6:20,24)This is the prophet who emphatically teaches that the kindom of God opens for those who give food to the hungry, who give something to drink to the thirsty, who welcome the stranger, who give clothing to the naked, who take care of the sick, who visit the imprisoned. (Matt 25:35-36). I don’t read him as saying there’s a heavenly reward later – bye and bye in the sky when you die, if you spend your days now “being good.” I read him as saying that at the very moment you reach out in kindness to meet another’s need, that IS the kindom of God. The very act of feeding the hungry IS stepping into the kindom of God. The moment you give drink to the thirsty, you are, in that moment, in the kindom of God. In welcoming the stranger, you are, right then, also welcomed into the kindom of God. Clothing the naked doesn’t earn you a ticket in – it IS being in. Caring for the sick, visiting the imprisoned doesn’t get you some reward extrinsically – it IS it’s own reward intrinsically. The kindom of God IS people helping each other. Being of service to others IS the treasure in heaven.

This is the prophet who tells his followers,

“Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.” (Matt 25:40)This is the prophet who teaches,

“If you wish to be perfect, go, sell your possessions, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me. . . . Truly I tell you, . . . it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kindom of God.” (Matt 19: 21-24)Given what Jesus’ life and teachings have been all about – at least, according to the Gospel writers – his entry into Jerusalem cannot be a claiming of Kingly prerogative. That’s not what this guy is about. That grandiose entrance can only be a subversion – an undermining of the very idea of Kingly prerogatives. As spiritual activist Casey Overton delightfully puts it, Jesus is trolling the class power structure by riding into town in mock triumph. Casey is drawing on the online usage of “troll,” meaning to post “inflammatory, inappropriate, controversial, or polarizing messages online for the purpose of cultivating animosity, upsetting others, or provoking a response.” Jesus, in other words, is being deliberately provocative.

That’s why the people are cheering, Casey suggests. Jesus’ inversion of norms is wildly entertaining – in a way not completely unlike the way, today, a drag queen’s performance inverts and subverts norms in a captivating and entertaining way. Fenton Bailey, co-executive producer of RuPaul’s Drag Race, says:

“To be a drag queen is to fly your freak flag, to live your life out loud, to not let other people dictate normal or to not edit yourself so that you fit in with other people.”The drag queen assumes an exalted, larger-than-life pose, ostentatiously parades with dazzling plumage and fanfare to the uproarious encouragement of the audience.

The drag queen’s reign lasts a few minutes, or maybe an hour, and then she returns to being “a regular dude.” Ordinary. As vulnerable as “those who cheered so loudly for her.” Perhaps more vulnerable -- because in our cisheteronormative society his transgressive alter ego makes him hated, feared, marked, targeted.

Jesus, too, in a different way, as he parades into Jerusalem, with a crowd shouting encouragement, is putting on a transgressive alter ego that subverts the very thing that it presents. Casey Overton writes:

“In the same way that transness in all its forms prefigures a world where gender is mutable, Jesus’ trolling transgression of class norms prefigures a classless world for and by the people.”The message for today? Today, as in Jesus’ time, we are a long way from justice, equality, and peace. Getting there will take a revolution. But this cannot be joyless work. Emma Goldman did not exactly say what has been oft attributed to her, but it does summarize a point she did make: “If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be in your revolution.”

We have a revolution to foment. We are called to overturn the structures that generate inequality, injustice, and violence. But let us not forget joy. Let us not neglect to have fun.

Sometimes the revolution IS a party. The party is the revolution and the liberation. Raucous drag performances are one way that partying, revolution, and liberation come together. Jesus also brings noisy celebration together with revolution and liberation.

That’s the way to see the message of the Palm Sunday story.

2022-04-09

UU Minute #82

Unitarians and Slavery: Leaders Amid Resistance

Unitarians were among the leaders in the movement for abolition of slavery. Joseph Priestly, then in England, preached a sermon denouncing the slave trade as early as 1788. Unitarian minister Rev. Charles Follen was a leading abolitionist in the 1830s. But monied interests in the North supported the slavery in the South. So Rev. Follen’s abolitionism led to his dismissal from the New York City congregation now called All Soul’s Unitarian. When Follen died in 1840, pro-slavery members of William Ellery Channing’s Boston congregation refused Channing’s request to host a memorial service for Follen.

A few years before that, in 1836, Rev. William Henry Furness, minister of First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia preached an abolitionist sermon to his congregation. Reverend Furness had begun serving that congregation (the congregation that Joseph Priestley had founded in 1796), when he was 22-years-old, and was 34 the day he stepped into their pulpit to preach abolition.

He knew it would be divisive. One of his most prominent members held 300 people enslaved. Furness’s stance split the congregation in half. Membership plummeted. Furness thereafter had armed guards at his side as he preached.

Later, Unitarian minister Theodore Parker encountered considerable controversy when he also began speaking against slavery and became a leading figure in the abolition movement. Parker took to keeping a pistol in his pulpit for his protection.

Many Unitarians – clergy and layfolk – committed their lives and fortunes to the cause of abolition. Yes, Unitarians were rancorously divided over the issue of slavery. Yet we were at least divided: while some other churches of the time were unified in support of slavery, many Unitarians were leading this denomination and this country toward a new moral awareness.

NEXT: Universalism: Beginnings

Unitarians were among the leaders in the movement for abolition of slavery. Joseph Priestly, then in England, preached a sermon denouncing the slave trade as early as 1788. Unitarian minister Rev. Charles Follen was a leading abolitionist in the 1830s. But monied interests in the North supported the slavery in the South. So Rev. Follen’s abolitionism led to his dismissal from the New York City congregation now called All Soul’s Unitarian. When Follen died in 1840, pro-slavery members of William Ellery Channing’s Boston congregation refused Channing’s request to host a memorial service for Follen.

A few years before that, in 1836, Rev. William Henry Furness, minister of First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia preached an abolitionist sermon to his congregation. Reverend Furness had begun serving that congregation (the congregation that Joseph Priestley had founded in 1796), when he was 22-years-old, and was 34 the day he stepped into their pulpit to preach abolition.

He knew it would be divisive. One of his most prominent members held 300 people enslaved. Furness’s stance split the congregation in half. Membership plummeted. Furness thereafter had armed guards at his side as he preached.

Later, Unitarian minister Theodore Parker encountered considerable controversy when he also began speaking against slavery and became a leading figure in the abolition movement. Parker took to keeping a pistol in his pulpit for his protection.

Many Unitarians – clergy and layfolk – committed their lives and fortunes to the cause of abolition. Yes, Unitarians were rancorously divided over the issue of slavery. Yet we were at least divided: while some other churches of the time were unified in support of slavery, many Unitarians were leading this denomination and this country toward a new moral awareness.

NEXT: Universalism: Beginnings

2022-04-02

UU Minute #81

Channing Resigns in Place

The paddlewheel steamboat Lexington, carrying 143 passengers, left Manhattan on January 13, 1840, bound for Stonington, Connecticut. In what is still the Long Island Sound’s worst disaster, the steamer caught fire and sank. Among the 139 lives lost was Rev. Charles Follen. The Unitarian minister, controversial for his ardent abolitionism deemed radical by the white power structure of that time, was returning from a lecture tour in New York to begin his ministry to our congregation in Lexington, Massachusetts – the congregation whose building he had designed, and which today bears his name: Follen Church.

Shortly afterward, William Ellery Channing received another visit from his friend Samuel Joseph May. May had come on behalf of the Anti-Slavery Society to discuss a public memorial service for Charles Follen, which the Anti-Slavery society wished to sponsor. May would prepare and deliver the eulogy. The appropriate place would be Channing’s Federal Street Church, where Follen had been ordained, and with Channing presiding.

NEXT: Unitarians and Slavery: Leaders Amid Resistance

The paddlewheel steamboat Lexington, carrying 143 passengers, left Manhattan on January 13, 1840, bound for Stonington, Connecticut. In what is still the Long Island Sound’s worst disaster, the steamer caught fire and sank. Among the 139 lives lost was Rev. Charles Follen. The Unitarian minister, controversial for his ardent abolitionism deemed radical by the white power structure of that time, was returning from a lecture tour in New York to begin his ministry to our congregation in Lexington, Massachusetts – the congregation whose building he had designed, and which today bears his name: Follen Church.

Shortly afterward, William Ellery Channing received another visit from his friend Samuel Joseph May. May had come on behalf of the Anti-Slavery Society to discuss a public memorial service for Charles Follen, which the Anti-Slavery society wished to sponsor. May would prepare and deliver the eulogy. The appropriate place would be Channing’s Federal Street Church, where Follen had been ordained, and with Channing presiding.

“All of that agreed, Channing ended by saying that he would, of course, have to ask the trustees of his society for permission for this use of their meetinghouse. Initially, they too agreed. Then, under pressure from anti-abolitionist members who had objected to any announcements at services of abolitionist meetings, they met without Channing present and voted, unanimously, to deny the use of the Federal Street Church for the Follen service sponsored by the Anti-Slavery Society. Channing was simply stunned.” (Buehrens)He decided he could no longer accept any money from this congregation he had served for 37 years. Many of his duties could transfer to the associate minister. Channing would not, however, give up the role of being their chief pastor. He would continue as the shepherd of their souls for nearly three more years until his own death in October 1842.

NEXT: Unitarians and Slavery: Leaders Amid Resistance

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)