God, the Verb, part 2

Whitehead gives us Process philosophy, and while Whitehead did write about the place of God in his philosophy, process philosophy did not become full-fledged process theology until the Unitarian Charles Hartshorne’s work expanded, extended, and revised Whitehead.

The main name in Process Theology is Charles Hartshorne. Born in 1897, Hartshorne was 103-years-old when he died in 2000. I never met him, though I could have. He was at our UU General Assembly as recently as 1994. Then 97-years-old, he participated in a seminar there put on by the Unitarian Universalist Process Theology Network, delighting attendees “with his lively, extemporaneous answers to their questions.” (Charles Hartshorne had one child, a daughter, Emily, -- who I did have the pleasure of meeting, -- in the sanctuary of Community UU, when she was visiting White Plains and attended one of our services a couple years ago.)

For Process Theology, God is not omnipotent. God is finite – changing and growing along with creation. Reality is made of events, not material substance. God, being finite and not omnipotent, doesn’t have full control of what happens. Rather, God engages with us in a process in which both we and God develop together. God changes.

God offers us possibilities the full meaning of which God doesn’t know. As we, God’s creatures, explore the offered possibilities, Creator and Creation alike learn, grow, develop, allowing new possibilities to be offered. Hartshorne held that people do not experience subjective immortality, but we do have objective immortality in that our experiences live on forever in God, who contains all that was. Just as you, throughout your life, build on your experiences, developing new experiences shaped by all prior experience, so, too, God, after your death, continues to build on your experiences. Your experiences continue to contribute to God’s new experiences for all eternity.

Yes, God transcends the world, but the world also transcends God. Yes, God creates the world, but the world also creates God. We are a part of God. Our growth is a part of God’s growth. God’s knowledge is the sum total of the knowledge of all life-forms – God’s desires the sum of the desires of life.

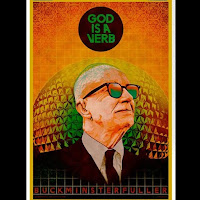

The emphasis on change leads to the idea that God is a verb – the active, creative principle in the universe. Buckminster Fuller, in 1940, wrote:

Here is God's purpose –The traditional notion of God as creator isn’t entirely off-base, says Process Theology. There really is a connection between the function of creating and the deep mystery, awe, wonder and sense of reverence that goes with the notion “God.” God the creator wasn’t entirely off-base – but God isn’t a person-like creator. Instead, God is creativity itself.

for God to me, it seems,

is a verb

not a noun,

proper or improper;

is the articulation

not the art, objective or subjective;

is loving,

not the abstraction "love" commanded or entreated;

is knowledge dynamic,

not legislative code,

not proclamation law,

not academic dogma, nor ecclesiastic canon.

Yes, God is a verb,

the most active,

connoting the vast harmonic

reordering of the universe

from unleashed chaos of energy.

And there is born unheralded

a great natural peace,

not out of exclusive

pseudo-static security

but out of including, refining, dynamic balancing.”

Here’s how the poet Wild Bill Balding puts it:

God is a verb, not a noun:Jean-Claude Koven writes:

'I am who I am,

I will be who I will be.'

dynamic, seething, active

web of love poured out,

given, received, exchanged,

one God in vibrant community

always on the move,

slipping through our fingers,

blowing through the nets we cast

to hold and name,

confine to nouns, to labels,

freezeframe stasis,

pinned like a butterfly,

solid, cold, controlled, lifeless.

'I am who I am,

I will be who I will be' -

not pinned down by names, labels,

buildings, traditions,

or even by nails to wood:

I am: a verb, not a noun,

living, free, exuberant,

always on the move.

“God is indeed a verb. He is not the creator. He is the ongoing unfoldment of creation itself. There is nothing that is not a part of this unfolding. Thus there can be nothing separate from God. . . . When we perceive God as a noun, we envision him as the creator, the architect of, and therefore separate from, his creation. Identifying ourselves as part of that creation, we see ourselves not only separate from our source but separate from each other and all other manifest things as well. . . . Once I viewed God as a verb instead of a noun, my perception of life shifted. Everything around me, manifest or no, became God. There was only God. When someone spoke to me, it was with God's voice; when I listened, it was with God's heart. As you begin to view God not as the creator but as the constantly changing dance of creation itself, you'll discover God in everything you see – including yourself.”UU minister Stephen Phinney puts it this way:

“I believe that the holy is in the process of giving and taking of the love we have. In other words, the holy or God is the process of interchanging love.”* * *

This is part 2 of 3 of "God, the Verb"

See also

Part 1: What Are You Saying When You Say "God"?

Part 3: Transitive, Intransitive, and God

No comments:

Post a Comment